Fourier series solutions VII - Solving differential equations with Fourier series

Let's see how we can sometimes use Fourier series to help us solve differential equations, including some partial differential equations. We will give two real-world examples, both involving a concept known as heat flow. In both cases, we will be dealing with two-variable functions, where our two variables are position

Heat flow

Let's first give a quick-and-dirty derivation of the so-called "heat equation". If you're already familiar with the heat equation, you can skip to the first example.

If you're still here, then suppose something one-dimensional is heating up and

We make two basic assumptions about the functions

Assumption 1: Newton's Law of Heating

At each fixed position

for some positive constant

Assumption 2: Energy accumulation

Suppose we look at a small chunk of the substance, of width

On the other hand, we will also assume that the rate at which energy in this little piece increases is proportional to the length of the piece and the rate at which the temperature is increasing in the piece.In other words, we will assume

for some positive constant

We can rewrite the above equation as

Our second assumption is therefore that

Combining these two assumptions

Using the above assumptions, we are suppose

We can combine these two differential equations to deduce a single differential equation that

Now substitute this into the second differential equation to obtain

We call this equation the Heat Equation, since it gives a model for how heat behaves in a one-dimensional substance.

Example: Hot wire

Suppose we heat a thin circular wire. Let's center a polar coordinate system on this wire and let

By our choice of coordinate

-

The function

satisfies the heat equation . -

For each fixed value of

, the function can be represented by a Fourier series in , i.e., for each value of there are complex numbers such that

Imagine

Before moving on, let's note that for each fixed value of

This will come up again at the very end of this example.

Solving this partial differential equation

Let's now use the method we employed with power series (and Frobenius series), i.e., substitute our candidate series into the differential equation. In this case, let's first compute

(We interchanged the infinite sum and the partial differentiation, which probably deserves justification.)

On the other hand, we can also similarly compute

and then

It follows that our Fourier series is a solution to our differential equation exactly when

Notice that, from the point of view of the variable

for every integer

When we looked for power series (or Frobenius series) solutions, we always found the coefficients of the mystery series needed to satisfy a recursion relation. Here, however, we see that something different has happened: the coefficients of our mystery Fourier series need to satisfy another differential equation!

You might think we've wasted our time, exchanging the problem of solving one differential equation for satisfying an entire family of new differential equations. Notice, however, that these new differential equations are ordinary, first-order, homogeneous, linear differential equations. If we fix

where

where

We've done it! Under the assumptions we've made for this problem, we've proven that the general solution is

Additional observations that foreshadow some cool things

It is common to describe the solution to a differential equation using two pieces of information:

- A description of the initial state of the system.

- A description of how the system evolves over time, i.e., of the dynamics of the system.

In our case, the first piece of information is the function

We can now rewrite our final solution, above, as

So now the initial state of the system can be seen as contributing to the solution. But we can do even better. Let's replace

where

Why did we do all of this? It turns out that our energy system (of a hot wire) is governed by:

- The initial temperature information, which is function

that is periodic (with period ). This is sometimes called the initial impulse. - A function

that determines how the energy moves through the system. This is sometimes called the impulse response or convolving function. - The integral above, which combines the functions

and , is called the convolution of the two functions. We will see that it can be seen as a "smoothed average" of the nearby temperatures, using the convolving function as a weighting function.

For now this all might seem a bit much, but as our theory develops it will prove remarkable prescient!

Example: Hot Earth

In this example, let us now imagine we've chosen a fixed position on the surface of the earth, and we let

-

The function satisfies the heat equation

. There is nothing special about the value of , other than to provide slight contrast with the previous example (and possibly make some numbers later on slightly nicer looking). -

The function

is periodic in with period . In other words, at any fixed position , the temperature should repeat annually. While that's not totally realistic, it's not an entirely terrible assumption. In places like Michigan, for instance, it tends to be cold every December and hot every July. Because of this assumption, we will assume we can represent by a Fourier series in , i.e., as

Note that in this example our function

We now substitute this proposed Fourier series into our heat equation, this time finding that

Once again, by the linear independence of the functions

or equivalently,

Solving this new differential equation

This new differential equation[1] is a second-order, linear, homogeneous differential equation. We can solve it using our methods from Linear Analysis I, although there's a good chance you never worked through an example with complex coefficients like this. Fortunately, the process is the same, so long as you're familiar with how to find roots of complex numbers.

In operator notation, we can write our new differential equation as

where

Suppose

In polar-exponential form, two complex number are the same exactly when they have the same polar distance and the same angle, up to integer multiples of

We now repeat the previous computation in the case

It follows that

Before returning to our Fourier series, in this case it helps to rewrite the above complex numbers in their real and imaginary parts. Using Euler's identity, we have

Similarly, we find that

Now that we finally have these roots, we can conclude that the general solution to the second-order differential equation

is

It turns out that, in our particular problem, our Fourier coefficients must have

Using the above cheat, we can now conclude that

As usual, if we set

Even better, if we let

The solution to our "Hot Earth" problem is therefore

Analyzing a special case

The above formula looks pretty complicated, so let's consider a special case in which a bunch of the terms greatly simplify. Suppose the temperature at the surface were given by

It follows that

We can simplify this expression and convert it into a function involving only real numbers, as follows:

A physicist might call this a damped and phase-shifted sine function. The term

To make things even nice, suppose we fixed our attention at position

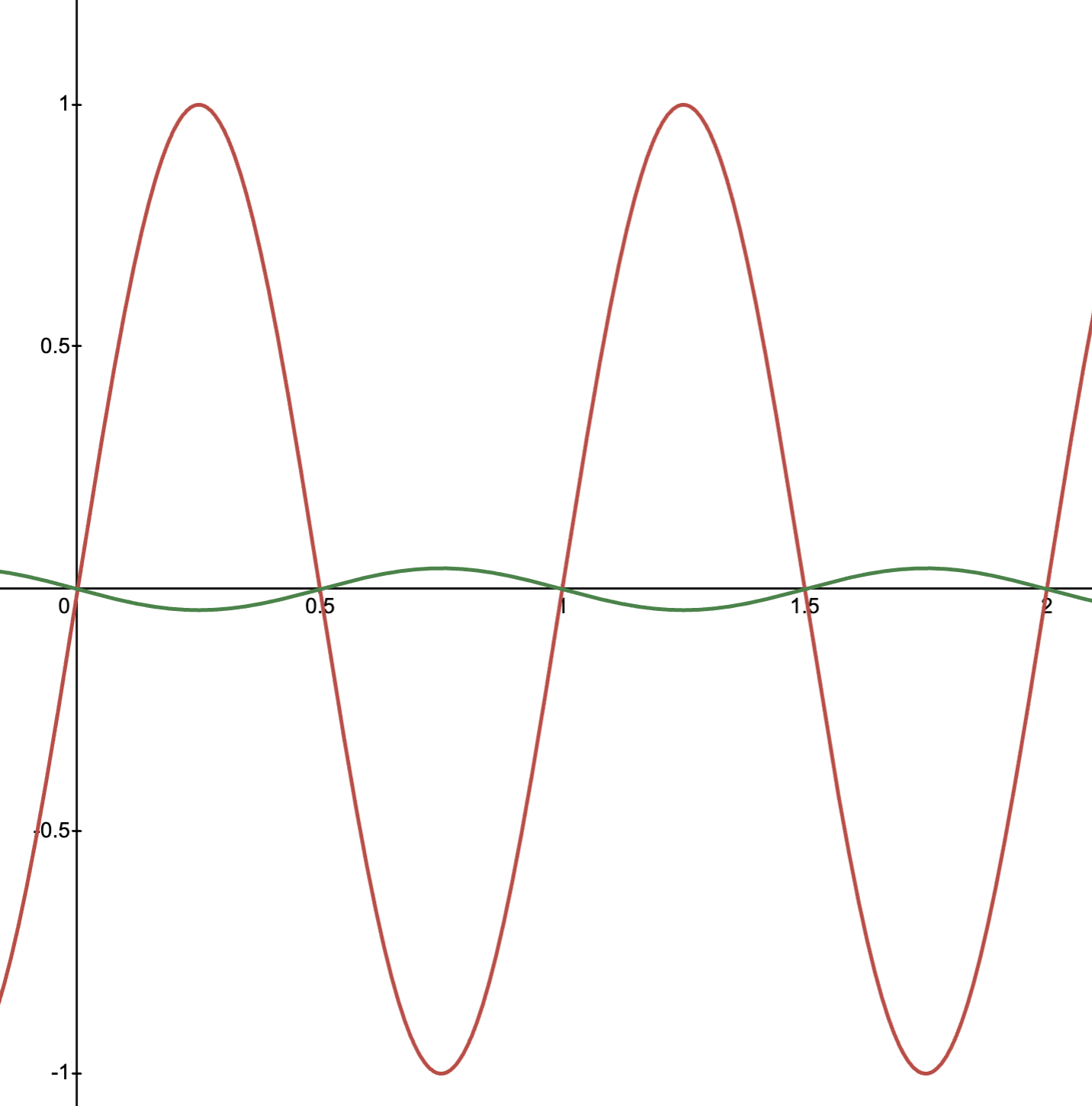

Comparing the graph of this function with the graph of the surface temperature, we see the following:

In other words, the temperature four feet down:

- Doesn't vary much.

- Is cool when the surface is warm and warm when the surface is cool.

This sounds a lot like how a cellar works, and it's the reason cellars are so useful!

A last observation

Before leaving this example, let's end by noting that the same trick used in the previous example can let us rewrite the general solution

where

is the impulse response (aka Green's function, fundamental solution, convolving function, ...).

There's definitely something going on here, and we'll see exactly what that is when we get familiar with the Fourier transform.

Suggested next notes

Fourier transform I - Pushing Fourier series to the limit

Really a family of differential equations, one for each integer

. ↩︎