Spectral sequences

This is very much a work in progress. It will likely need to go through many iterations, be broken into separate parts, etc. Read at your own risk!

Some background

... after Leray's lecture on this work, Whitney rose to say that, after this talk, he no longer understood algebraic topology, and, if homology was going to be like this, he would have to study other parts of mathematics.

Ces notions furent mal accueillies en Amérique au moment de leur publication. C'était trop di cile. Les Mathematical Reviews demandèrent 'À quoi ça peut servir?'

These notions were poorly received in America when they were published. They were too difficult. The Mathematical Reviews asked, 'What good is this?'

Origin of the term "spectral sequence"

A question that often comes up is where the term “spectral” comes from. The adjective is due to Leray, but he apparently never published an explanation of why he chose the word. John McCleary (personal communication) and others have speculated that since Leray was an analyst, he may have viewed the data in each term of a spectral sequence as playing a role that the eigenvalues, revealed one at a time, have for an operator.

... the consequences were announced in a series of three Comptes Rendus notes. In the first note the term spectral sequence (suite spectrale) makes its appearance. It applies to the homology spectral sequence for which the terms spectral ring or spectral algebra of Leray and Koszul did not apply.

They have a reputation for being abstruse and difficult. It has been suggested that the name ‘spectral’ was given because, like spectres, spectral sequences are terrifying, evil, and danger ous. I have heard no one disagree with this interpretation, which is perhaps not surprising since I just made it up.

The basic goal

A common scenario behind many (but not all!) applications of spectral sequences is to compute

- (co)homology of some space

- (graded) algebraic invariant of some group/ring/module

- (hyper)cohomology of a double complex

For simplicity, let's assume

Suppose now

For example, the grading itself can give a filtration, where

In any case, from a filtration

Now, it's sometimes the case that we can recover

Before moving onto the definition of a spectral sequence, note a filtration

Although it might seem odd that we've chosen to write the bigrading this one, it's for historical reasons. The degree

A (first quadrant, cohomological) spectral sequence is a sequence of differential bigraded objects (say, vector spaces)

We sometimes call

Notice that for any fixed coordinate

A spectral sequence

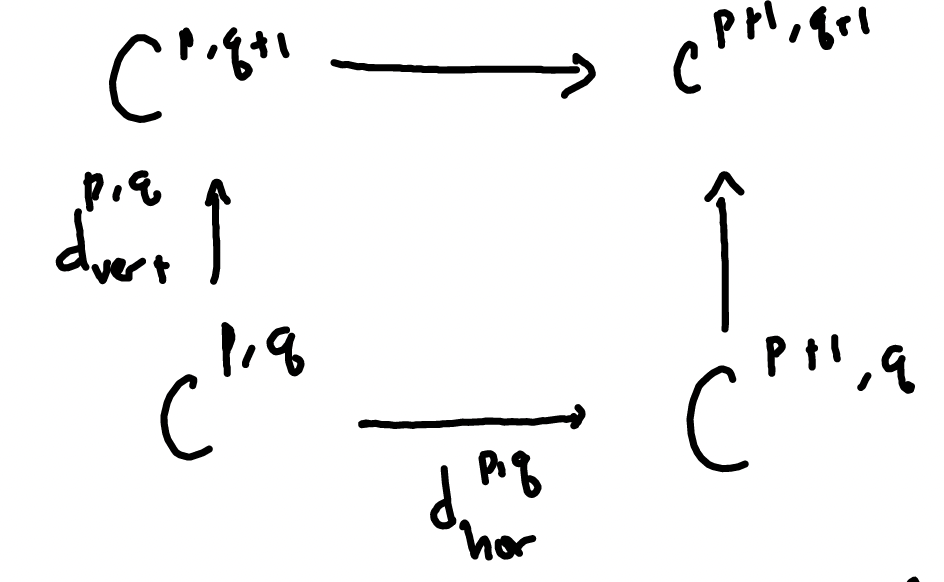

The basic idea for a double complex

Suppose we start with a double complex

Let's assume for simplicity that the sequares anti-commute, i.e., that

and where we use the differential

Now consider the cohomology

There are two obvious filtrations we can put on

Example: The Snake Lemma

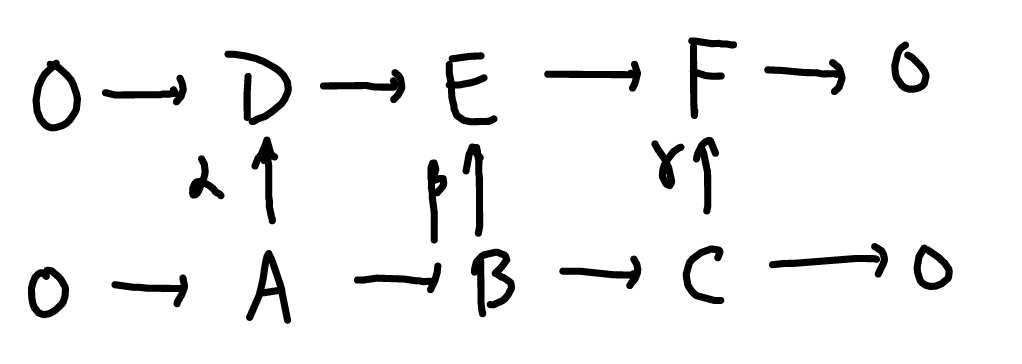

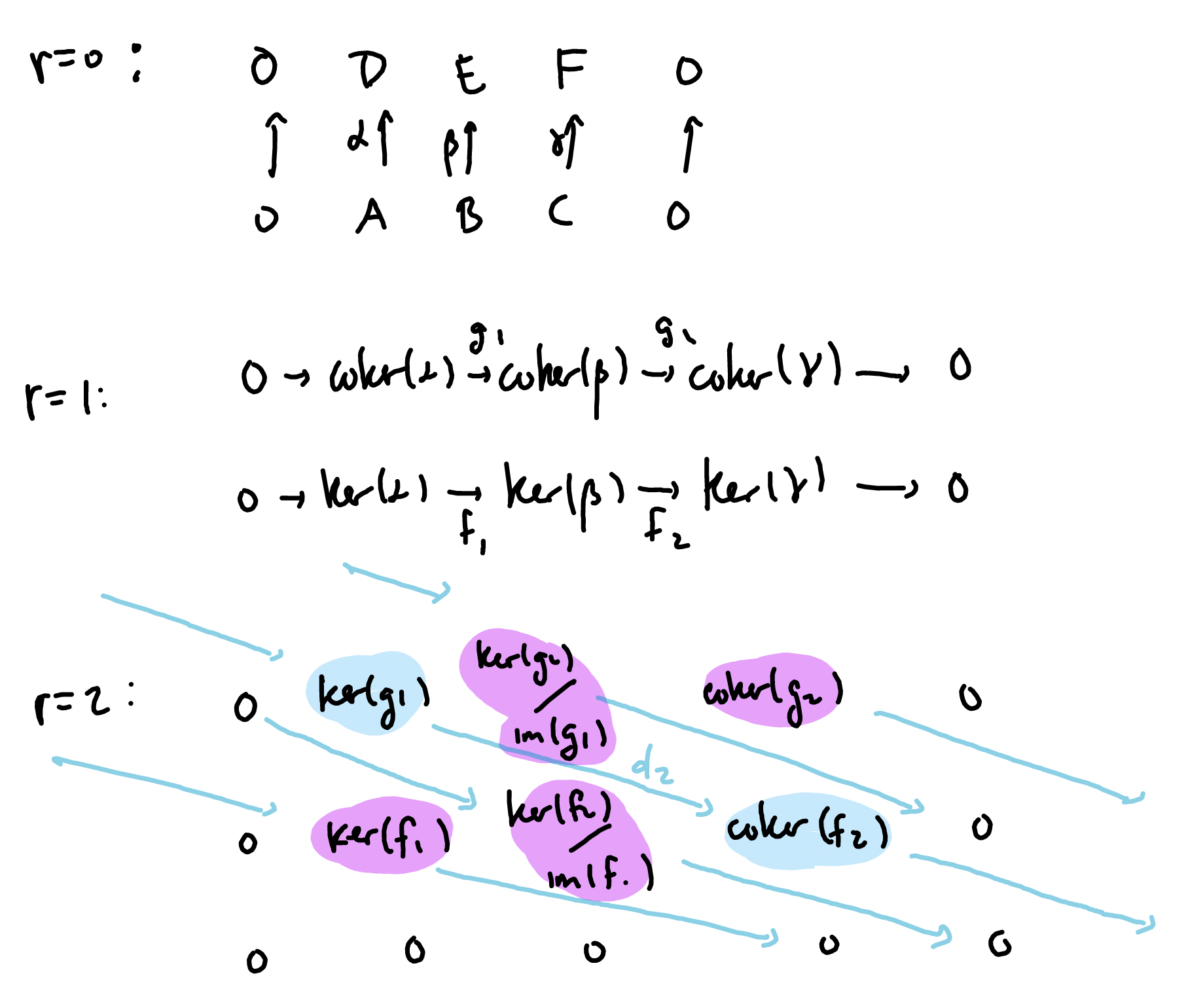

Suppose we begin with the commutative diagram below, in which the rows are exact:

Extend this to first-quadrant double complex by putting 0s in every other position and trivial maps where needed.

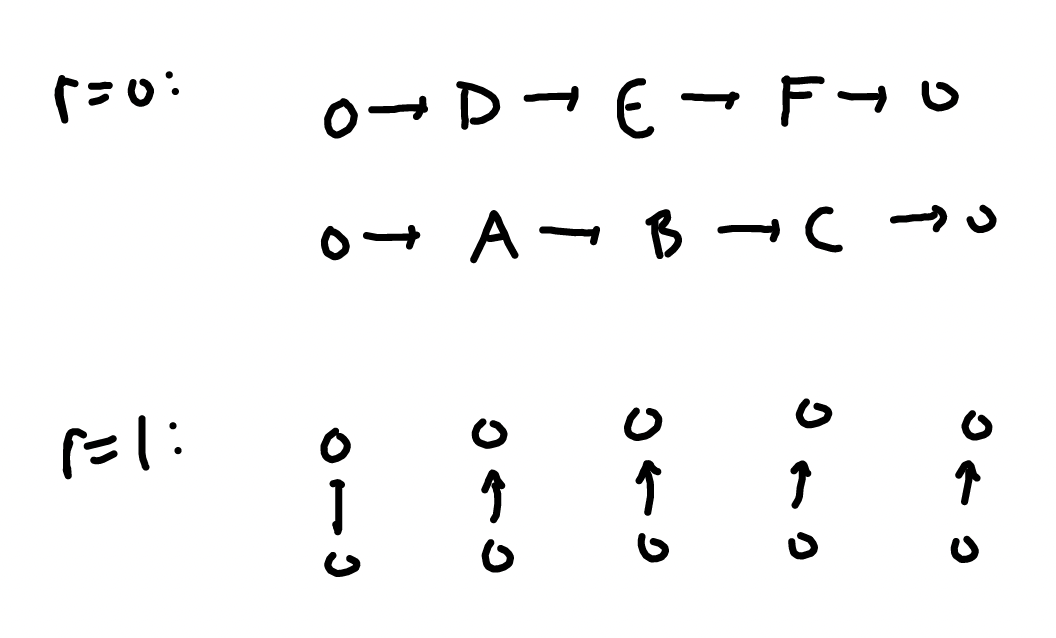

Using the horizontal arrows produces a spectral sequence with rightward orientation. The pages

We can say that the spectral sequence collapsed at

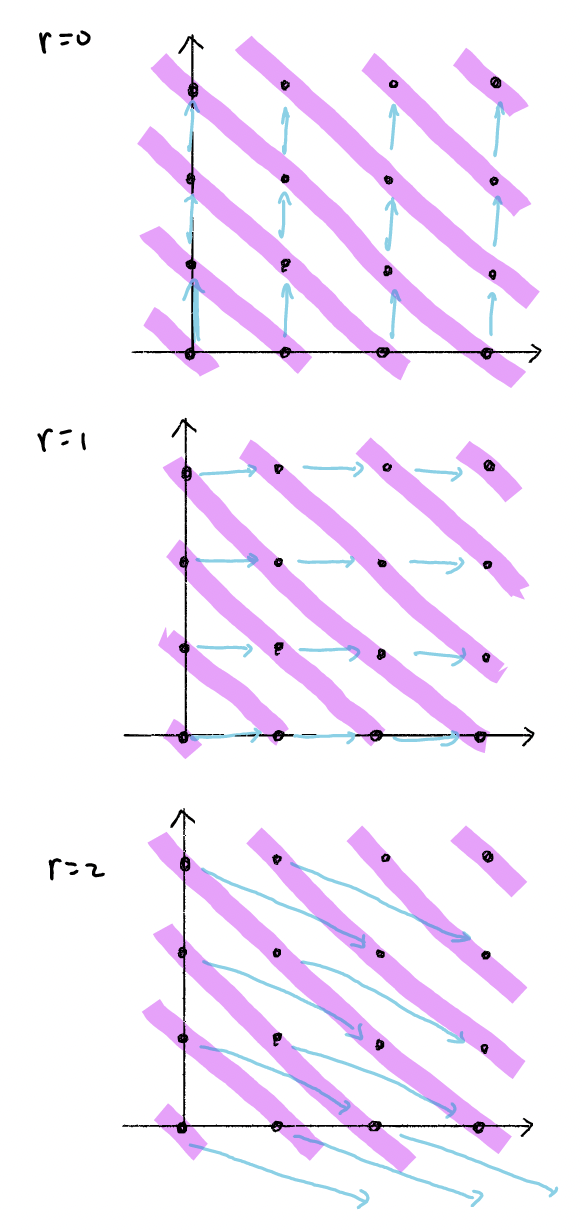

On the other hand, using the vertical arrows in the original double complex produces a spectral sequence with upward orientation. The first three pages of the spectral sequence now look as follows:

The terms highlighted in pink have stabilized at this point, as they do not (nor ever will) have nontrivial differentials mapping to/from them. The terms in blue will stabilize on the next page.

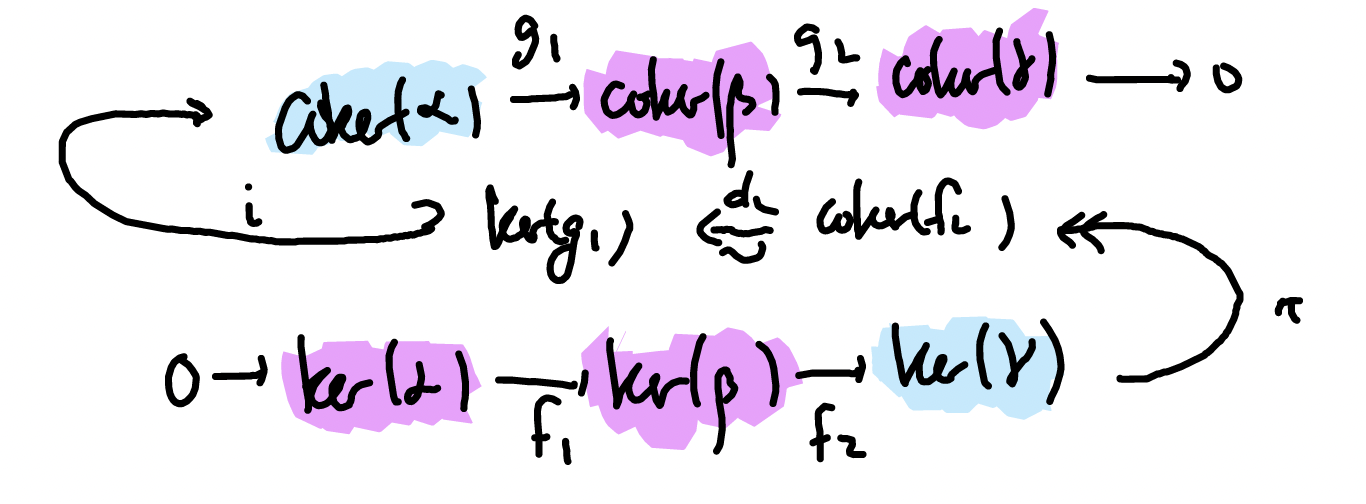

Now, this spectral sequence also converges to

where the connecting morphism is

Example: The (Weak) Five Lemma

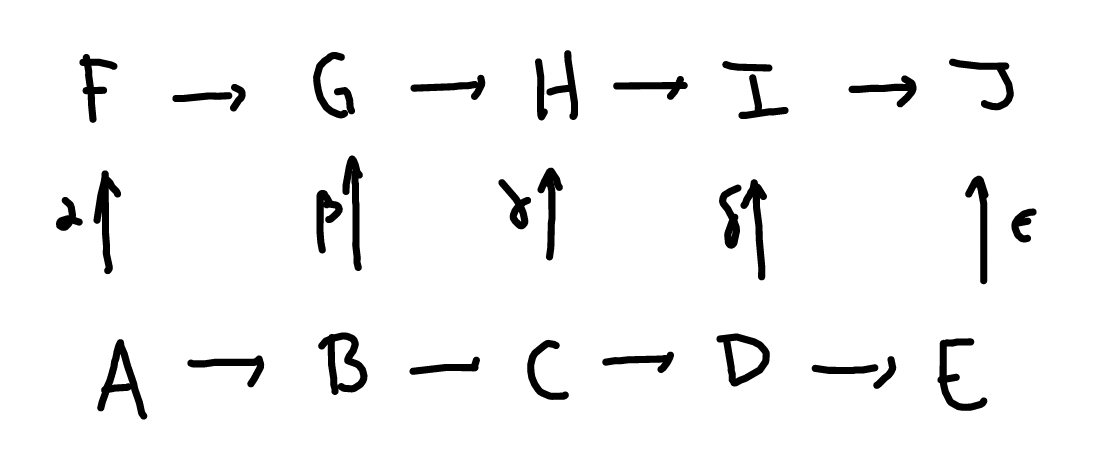

Suppose we begin with the commutative diagram below, where the rows are exact and the outside four vertical arrows are isomorphism. (This second condition can be weakened.)

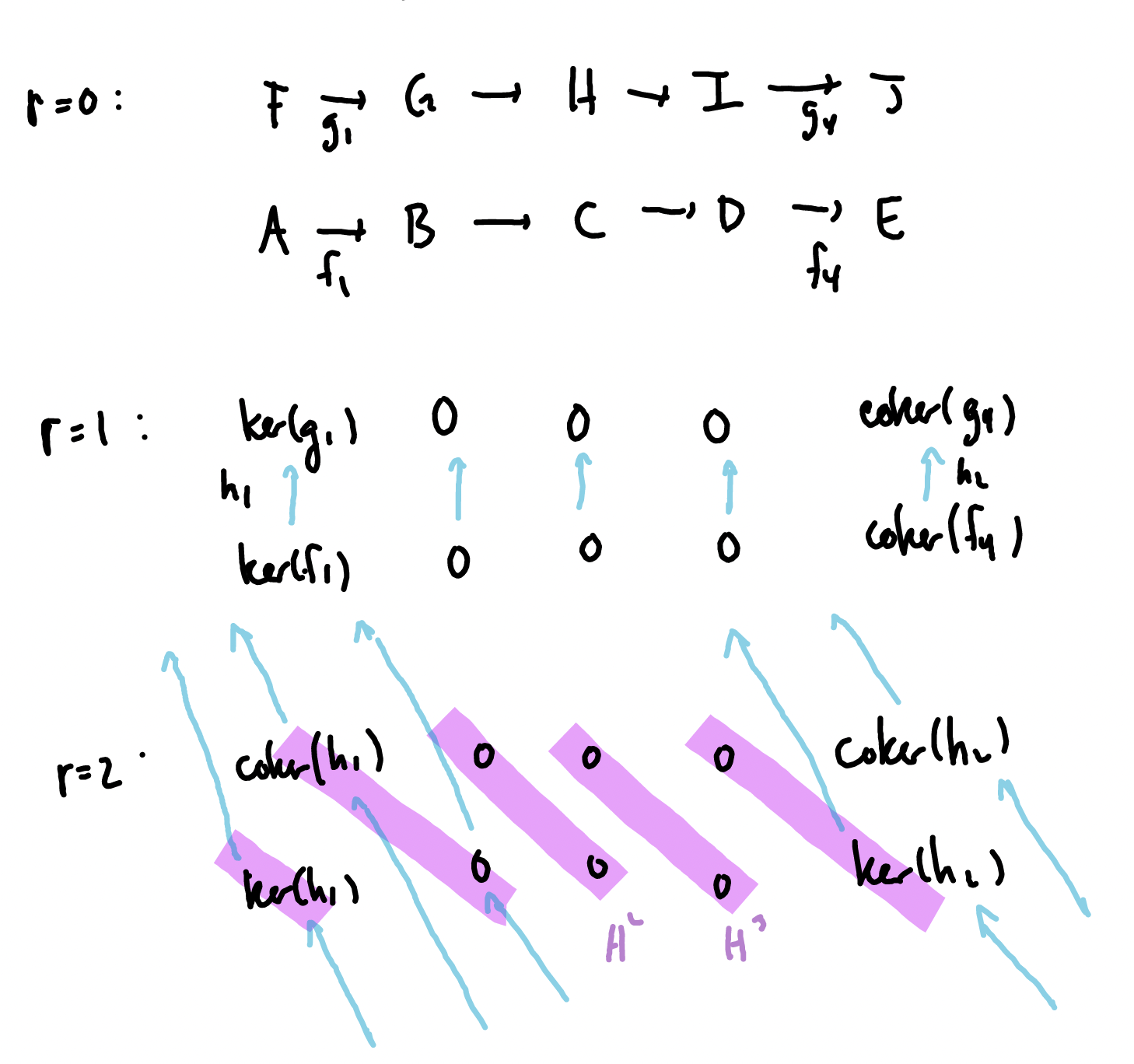

Let's repeat the same strategy from the previous example. Beginning with the rightward orientation leads to a spectral sequence with the following first three pages:

Notice that this spectral sequence has collapsed at

If we now instead consider the upward orientation, we find a spectral sequence that converges at

Since we earlier concluded

Example: The Grothendieck spectral sequence

This isn't really an example so much as hint at another scenario in which spectral sequences appear.

Suppose

It makes sense to ask how the right derived functor of the composition

For each object

that converges to

References

[[Chow - You Could have Invented Spectral Sequences.pdf]]

[[McCleary - A History of Spectral Sequences.pdf]]

[[Bott-Tu - Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology.pdf]]

[[Kato - Heart of Cohomology.pdf]]

[[McCleary - A Users Guide to Spectral Sequences.pdf]]

[[Vakil - Puzzlin Through Exact Sequences.pdf]]

Vakil - The Rising Sea.pdf